Andrew Leslie Phillips

"In Australia I sickened of the urban life, the crowded rush to work in the mornings, the tiresome after-work booze-ups at the pub and the predictability of my future. I’d spent five years in advertising. I was now an account executive doing the bidding of my corporate masters, selling the American dream that had become Australia’s. My initial fascination had become a curse and no longer was I interested in the shallow search for unique selling points and catchy phrases, the pretty pictures and the jingles, selling capitalism to the masses.

As I observed the careers of my fellow workers grinding relentlessly toward retirement, I felt a dark cloud descending and as it thickened around me I struggled to find a way to escape. I thought about inland Australia where mining companies paid well and life was rough in the desert. I considered joining the army, something to initiate and toughen me and help me escape the malaise I felt. But the war in Vietnam was in the headlines every day and Australians were dying in a distant struggle that made no sense to me and I quickly dropped the idea. And then, one day, an old school friend suggested Papua New Guinea ..."

So begins a blog written by Andrew Leslie Phillips who spent several years as a 'kiap' on Bougainville. Continue reading his story here.

His description of Kieta brings back lots of memories:

"Kieta was perched on a narrow ribbon of land skirting the harbour. Pok Pok Island loomed offshore, protecting the harbour from the squalls and storms that sometimes tore in from the east with great ferocity. Pok Pok means crocodile in Pidgin English and the island had the shape of a huge crocodile laying flat on its belly on top of the sea, its huge head jutting out to the south, its tail tapering to the north. It was inhabited by local natives who paddled their small canoes loaded with copra, fish and vegetables for sale in Kieta.

Jimmy Wong’s Chinese trade store was at one end and of the settlement and Kieta’s hospital, a series of grass huts with tin roofs, was at the other. Between were administrative buildings huddled under the ubiquitous coconut trees that curved and swayed against the cloudless sky providing dappled shade from the tropical sun. Houses with enclosed verandahs protecting the inhabitants from the teeming malarial anopheles mosquitoes, crept back from the shoreline and climbed steeply up the mountains offering a fine view of the picturesque harbour. A thick green blanket of jungle, a carpet of dense undergrowth and a profusion of tropical forest trees swathed in creepers and vines and screeching wildlife, accelerated rapidly into the clouds toward the inland spine of the island.

The Kieta Club, a whites-only club where the local expatriates drank too much, took pride of place at the centre of the small community and near the shoreline was the Kieta Hotel where I stayed when I first arrived.

It was run by a small jolly Aussie fellow who wore colorful sarongs and recruited natives from the Mortlock Islands over the horizon, an idyllic group of small islands on a single atoll, north east of Bougainville and part of the Solomons.

The Mortlock islanders are Polynesians with straight hair and slim bodies who fitted the stereotype created by the French artist, Paul Gauguin who’d lived in Polynesian Tahiti in the latter part of his life. They were unlike the Negroid, stocky, blue-black Bougainville natives.

This was my first posting in Papua New Guinea. I was 23 and far from my former life in Australia. It was almost my dream come true. Almost because I was acting as district clerk, tied to a desk and a formidable row of file cabinets, answering directly to the District Commissioner.

The adventures I sought in the jungle would have to wait for the return of the regular clerk who was on furlough for six months and I was his replacement.

I bunked in a back room at the Kieta hotel with three other patrol officers who were new inductees to the Bougainville District administration. There’d been an influx of officers because copper and gold had been discovered in Bougainville’s central highlands.

Soon landsmen and surveyors would arrive to negotiate purchase of large tracts of beach front for a massive port to export the minerals. And thousands of acres of virgin jungle high in the mountains to mine the minerals.

It would be patrol officers who’d accompany the land surveyors, magistrates and land wardens, to negotiate land exchanges to begin one of the world’s largest mining ventures.

One morning as we assembled for breakfast of fresh papaya with a squeeze of lime juice, followed by bacon and eggs served by the handsome sarong clad waiters, a stranger approached. He was an Australian but unlike we patrol officers in our khaki shirts, shorts and long white socks, was dressed native style wearing sandals and a sarong we called a lap lap, wrapped around his waist and worn like a skirt.

His name was Barry Middlemiss and he was the plantation manger at Arawa and worked for Kip McKillop who’d been a coastwatcher during the war years and owned a one-thousand acre copra plantation not far from Kieta. The plantation was renowned for its outstanding orchid collection of more than one-thousand varieties.

The coast watchers were Allied military intelligence operatives stationed on remote Pacific islands during World War II to observe enemy movements and rescue stranded Allied personnel. There were about 400 Coastwatchers in all—mostly Australian military officers, New Zealand servicemen, Pacific Islanders and escaped Allied prisoners of war.

In August 1943, Lt John F Kennedy of the United States Navy and twelve fellow crew members, were shipwrecked after their boat, the PT-109, sank. An Australian coastwatcher, Sub-Lt Arthur Reginald Evans, observed the explosion of the PT-109 when it was rammed by a Japanese destroyer. Evans dispatched two Solomon Islander scouts in dugout canoes. The scouts found the men and Kennedy scratched a message to Evans on a coconut, describing the plight and position of his crew and the rest is history.

Middlemiss sat. He observed us with a mix of disdain and envy. He’d “gone native”, siding with the locals, and was helping organize resistance against the inroads of the copper company and the administration. He was cut-off from his fellow countrymen and seemed hungry for fellowship but his demeanor was aloof and his conversation laced with disdain toward the Australian support for the copper company.

It would take me some time to understand Middlemiss’ attitude for I was naïve and unfamiliar with the politics, greed and the devastation our work as patrol officers supported. We were handmaidens to the mining industry and, though unaware at the time, were sowing the seeds of a revolution the likes of which Australia and her colony had never seen.

In the district office I filed the paper work that greased the wheels of the mining venture. More and more white strangers were fronting the bar at the Kieta club. Blasé Americans and Aussies in new Toyota Landcruisers trickled into town and disappeared into the jungle. There were murmurings of unrest in some inland villages and the police contingent at district headquarters was increased.

I became friendly with the land warden who was responsible for arbitrating the sale of land to the mining venture. He was much older than I, a fit and friendly fellow who eagerly awaited the arrival of his young girlfriend from Australia. On weekends Hec and I headed for a bay near Aropa airstrip that paralleled the coast, to swim in the surf that beat against the rocks and crashed on the black sand beach.

We floated beyond the break in the warm sea looking back at the beach, the palm trees fringing the rugged coastline and the steeply rising foothills which quickly climbed higher and higher into the cloud forest. To the north we could sometimes see Mount Bagana, a steaming volcano, which sat central in the island.

We talked about home and a life devoid of female company and I realised I was lonely for my Australian girl friend, whom I’d left back in Melbourne. Soon I was to write and encourage her to leave her nursing job to come marry me in the islands.

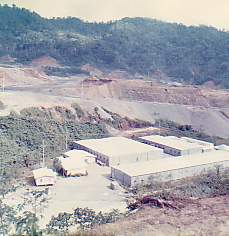

Hec’s job as land warden, was to wrest land from the natives and settle on a price. The mining company was a British based conglomerate, Conzinc Riotinto (CRA), which amalgamated with an Australian partner and employed American engineering outfits to install the infrastructure of what would soon become the world’s largest open-cut copper mine deep in the mountains at Panguna in the heart of Bougainville Island.

When I’d first arrived on Bougainville, the road to Panguna was a treacherous track that climbed precipitously through primeval rain forests. The Moroni lived in clusters in grass huts in clusters but soon their ridge-top homes would be torn down as excavation of the mine site proceeded.

There were about twenty known language groups on the island, all with their own unique customs. The Boungainvillians passed land ownership through the women. It was a matrilineal society and the women held great sway.

In the early land struggles, the women were on the front lines to try stop the mine from destroying their home. Near Kip McKillop’s plantation at Arawa, the Rorovana women, bare breasted, wearing laplaps and holding their children, stood between the government and their land, fighting to retain their birthright.

The pictures of that initial fight were spread across the front pages of Australian newspapers and alerted the world to the nascent struggle. But I think it was the naked breasts more than the rights of the locals that garnered the publicity for little was seen of the press in those parts after that, during the early development of the copper mine.

I was beginning to understand what Barry Middlemiss, the strange outsider I”d met months before, was all about and I admired his courage and lonely struggle to protect the local natives from the onslaught of the mining venture.

When the district clerk finally returned to rescue me from the tedium of office work, I learned I would be posted to Boku, a distant inland patrol post in the south of the island.

I pined for companionship and my girl friend back in Melbourne as I sat on my verandah at nights looking out over Kieta’s harbor, marveling at the unspeakable beauty of those tropic nights, watching canoes leaving to fish, their lanterns glimmering like tiny stars on the black sea. I wrote Libby a letter asking her to marry me and after a few excruciating weeks of waiting, her letter arrived saying “I do!”.

On a clear tropical evening in Kieta, the District Commissioner did the honours. His black car collected us and drove, ceremonially through town to his house, which was mounted high on a hill with the best view of the land. The District Commissioner had gout that day and hobbled around on a crutch; a long white stocking covered one foot that lay propped on cushions on a stool while he presided over ceremonies from a chair while his wife and daughter prepared the savories.

Later we would celebrate with fresh sea food and copious strong drinks at the home of a senior officer. And then retire to our conjugal bed in our standard issue domicile to begin our new life together.

Soon afterwards I was posted out of headquarters to a bush posing. Libby and I boarded a coastal trading vessel and sailed south, to the bottom of the island, to Buin. And then drove inland, crossing seven rivers with no bridges, fording the waters in a four-wheel drive Landrover, until finally we reached the inland patrol post at Boku.

The officer in charge was a tall, bird-like, eccentric fellow who favored brief shorts and bare feet. I’d read of Bob Hoad’s legendary exploits in the Fly River delta in south-west Papua. He’d conducted one of the last great exploratory patrols that had lasted nine months and his patrol reports were lengthy and detailed.

Bob Hoad, the barefoot kiap - click here and here for some old footage

In the library in Australia at ASOPA, I’d poured over his reports with wonder and admiration. Now I stood in front of him at this lonely outpost where my wife was the only woman among three white men. I noticed how he avoided my eye and seemed unable to take his gaze of my attractive young new wife, creating a great unease in my heart. But there was to be no hanky-panky at Boku in the year we spent though, till the end, I was never able to communicate with my senior officer.

Bob Hoad led Libby and I to our new home, a large thatched grass house with bamboo shutters and a tin roof. No running water and an outback toilet, a simple wood cooking stove, kerosene lamps. Gecko lizards, friendly green creatures that made clicking sounds as they crawled up the walls clinging with suction feet pads, some transparent so you could actually see their innards. It was a lonely and desolate green place and our first home together.

Nearby, across the Pureata river, was a construction camp where engineers and machine operators were installing a road to connect the patrol post to the copper mine at Panguna. Once a week we’d visit to drink beer, sit under the stars and watch a movie. These visits became the highlight of our week. They were a hardy group of Aussies, polite toward me and my wife in that outlandish place. We became friends and they offered relief from the sultry, introspective senior officer whose eyes that devoured my wife and left us both uncomfortable.

We went through months of loneliness at Boku. The highlight of the month was receiving stores we’d ordered and were shipped by boat and then truck to Boku. And the occasional visit from a patrol officer friend who flew his own plane and once visited. I studied film script writing by correspondence and pined for more social life and stimulation.

The patrol post office was another grass hut overlooking the Puriata River. In the rainy season, ferocious thunderstorms rolled in at noon like clockwork. Usually I made it to my house for lunch, about one hundred meters from the office, before the storm clouds opened and the deluge began.

On one such occasion I was resting, stroking the cat which lay on my chest when there was a massive explosion that rattled the tin roof and propelled the cat high into the air screeching in fear, leaving her claw marks etched in my chest.

When I returned to the office I saw the tall coconut tree that shaded the office, cleft down its center from the lightening bolt responsible for the ruckus. The electrical charge had raced down the tree’s trunk splitting it asunder and into the soil tracing the outline of the roots as if a machine gun had strafed the ground.

After these storms, the humidity lessened and the air smelt fresh and clean creating a magical atmosphere in the evenings when we sat on the verandah enjoying a beer. On one such evening the man who ran the patrol post’s generator providing electricity in the evening till 10 pm, sauntered towards us and beckoned. He opened his fist to show me what looked like an axe head the size of a matchbox and asked if I wanted it. “Olsem wanem” I asked – “what is it?”

“Ol i kolim marlio ston” he said. “Olsem wanem dispela marlio ston – i cum long sampela hap we?’ – “ its called a malio stone” he answered. “What is it – where is it from?”, I’d asked. “Dispela ston i pundaun na brukin diwai taim ples bilong klaut i pairap” – “the stone comes down and breaks the tree when lightening strikes” he said.

“Wanem nem bilong dispale samting” – “what is it called”, I asked a second time trying to fathom the origins of the strange looking artifact which by now I was holding, rubbing my fingers on its smooth surface. It was dark gray in color with a sharp edge on one end and curved and swelled towards the back where it was round and smooth. I had seen nothing like it and wondered if perhaps it could be some kind of ancient tool. And yet it did not seem hard or heavy enough to be an axe head and it was certainly not an arrowhead.

“Dispela ston, oli kolem malio ston” – ‘this stone is a marlio ston”, the man answered again and went on: “Olgeta taim klaut I pirap, dispela marlio ston I pundaun na brukim namel dispela diwai na mipela painim em long insait na klostu long diwal.

The man was telling me that during a thunderstorm, the stone came from the lightening in the clouds and split the tree in half and that people found them in the tree of nearby. I took the stone and placed it in a safe place and next day asked some of the Bougainvillian police stationed at the patrol post about the stone. They confirmed the story.

Years later in New York City, I told this story to a friend of mine from the small Himalayan country of Bhutan and he turned to me with an excited grin exclaiming: “oh a thunder stone – very special stone – it has special properties – we have them in Bhutan!”.

When I brought the stone, which is my oldest possession and which I had carried with me for more than thirty years, to show it, he took the stone and held it with reverence and asked if he could borrow it. “It is special”, he said and would protect and bring good luck.

It was soon after this that I realized that perhaps the adventure I had sought as a patrol officer was not going to materialize. Independence for Papua New Guinea was now the prime objective of the administration and our work was more and more involved with supporting district government and local councils. Patrol officers were now glorified clerks and accountants and I knew I had to move on.

It was 1969 and the Vietnam war was slowly worsening, taking more lives. Mankind had landed on the moon. A president and his brother had been shot and a black sage called Martin Luther King, murdered and the uncompromising outrage of Malcolm X had been stamped out.

All this I heard on short-wave radio broadcasts I monitored in our grass hut. I felt remote and cut-off from the world. I could feel the end of an era. I did not think of myself as colonial. Like most in the administration I was teaching the locals how to do what we did. In fact we were all here to work ourselves out of a job eventually, to implement development and growth and spread the good news of democracy and capitalism.

But the days of exploration, some might say exploitation, and true adventure in Papua New Guinea, had passed. After two years in the field I decided to resign my commission and capitalize on my advertising background and try garner a job in the Department of Information and Extension Services as a radio journalist in one of the fifteen radio stations run by the administration." (Link to the original article and another article which duplicates much of the first).

P.S. Andrew's ex-wife wrote and self-published "Tupela - A time in an untamed paradise" which is a memoir and love story of Libby, a young bride, and Andrew, the most junior patrol officer, who begin their marriage at Kieta, a tiny town on the island of Bougainville. Postings to other districts in PNG follow, including Rabaul, where they survive the murder of District Commissioner Jack Emanuel, a giant earthquake and tsunami, and a visit to a Tolai village with swirling Dukduks. What they can't survive are changes to their relationship. Their life together is unravelling just as the colonial power in Papua and New Guinea is. They try to hide the truth as they enjoy the excesses of life in a country they both love.

Read also the description here.

For a full profile of Andrew Leslie Phillips, click here.

frsOwCWk~%24(KGrHqJ%2C!jYEv1%2B0FPMLBMNuQBPhiw~~_12.jpg)